By James Kwak

[Updated with Mnuchin’s position on charitable contribution deduction.]

I wrote two days ago about the fairy tale that you can lower tax rates for the very rich yet avoid lowering their actual taxes by eliminating those mythical beasts, loopholes and deductions. The basic problem with this story is that, at the very high end of the distribution, deductions and exclusions (with the possible exception of the deduction for charitable contributions) just don’t amount to very much as a percentage of income. Therefore, eliminating those deductions may increase rich people’s taxes by tens of thousands of dollars, but that is only a tiny proportion of their overall tax burden, and not enough to offset any significant rate decrease.

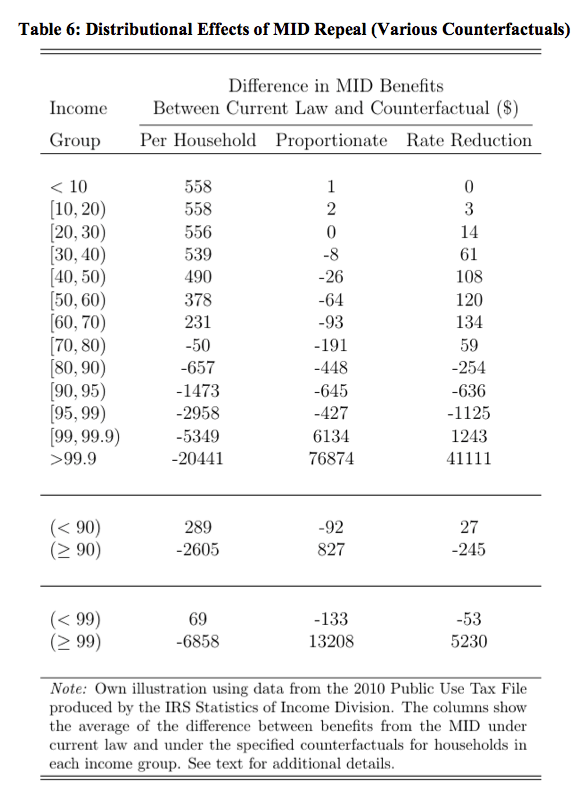

Unlike me, Daniel Hemel and Kyle Rozema are actual tax scholars (Hemel has a blog on Medium), and their detailed research largely tells the same story. They have a forthcoming paper that analyzes the mortgage interest deduction (MID) and shows that, while it is worth more dollars to rich people than poor people (for all the well-known reasons—bigger houses, higher marginal rates, itemizing), the MID causes people in the top 1% to pay a larger share of the overall tax burden. Therefore, eliminating the MID and using the increased tax revenue to reduce tax rates for everyone (what Mnuchin proposed in concept) would be a large windfall for the top 0.1% and a small windfall for the rest of the 1%.

The numbers are in the last column of this table:

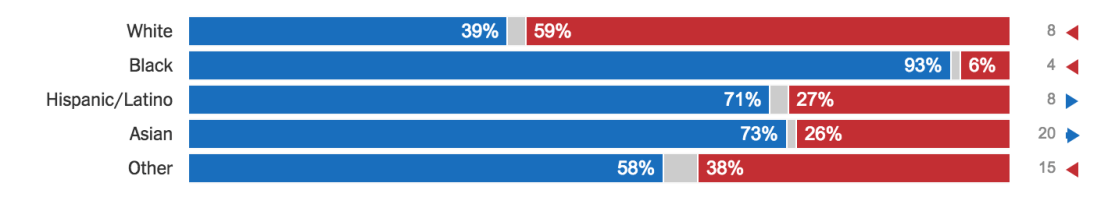

The respective roles of race and class in this year’s election are a highly contentious issue. I’d like to add to that contentiousness as little as possible while pointing out that this race-based framing isn’t really supported by exit poll data. I want to get ahead of the vitriol by stipulating that the exit polls don’t provide conclusive evidence for either side.

The respective roles of race and class in this year’s election are a highly contentious issue. I’d like to add to that contentiousness as little as possible while pointing out that this race-based framing isn’t really supported by exit poll data. I want to get ahead of the vitriol by stipulating that the exit polls don’t provide conclusive evidence for either side.