By James Kwak

The House of Representatives is considering a bill that would change the tax treatment of venture capitalists’ income (and that of private equity fund managers as well). Currently, VCs typically are paid “2 and 20” — that is, an annual fee of 2 percent of assets, plus 20 percent of profits. For example, let’s say a fund starts out with $200 million. Most of that money is invested by the fund’s limited partners — pension funds, endowments, insurance companies, the usual suspects. After ten years (roughly the average life of a VC fund), the investments made by the fund are now worth $400 million — a pretty humdrum return of 7 percent per year (before fees). The venture capitalists themselves will earn about $14 million ($200 million x 2% x 7 years)* plus $40 million (20% x ($400 million – $200 million)) equals $54 million. (Note that they earn that $40 million even for doing worse than the stock market’s long-term average return.) The limited partners get what’s left over after those fees. And before you start crying for the VCs, remember that a typical VC firm will have multiple VC funds going at once.

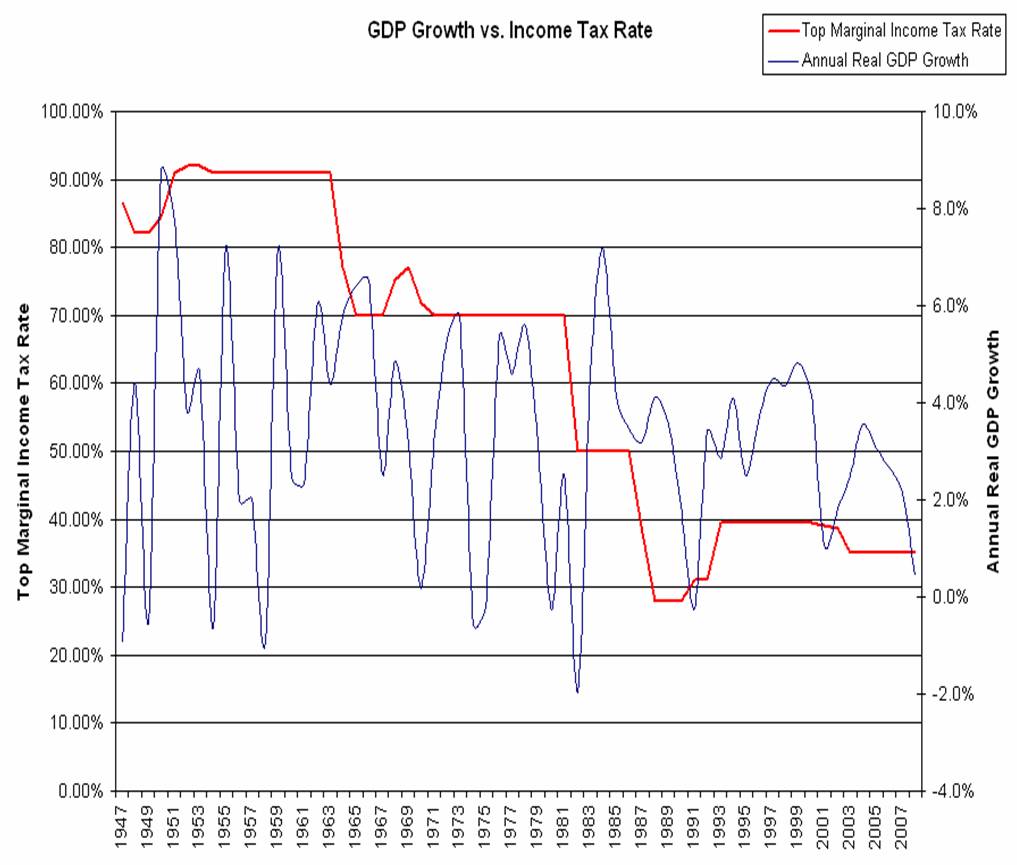

Right now, the $14 million is taxed as ordinary income, but the $40 million is taxed as capital gains — that is, at a tax rate of 15%. The bill would tax the $40 million as ordinary income (actually, 75% as ordinary income and 25% as capital gains), for an effective tax rate of about 35%.

The current tax treatment has never made sense to me. The lower rate on capital gains is supposed to provide an incentive for capital investment.** This is why, if you buy stock and sell it more than a year later, you pay tax on your gains at a lower rate. So clearly the actual investment returns on money invested in the VC fund should be treated as capital gains — but not the VCs’ 20 percent fee, since that’s compensation for fund management services, not returns on their investment. (VCs typically invest their own money in a fund, but it is only a small fraction of the whole, and no one is debating how that money should be treated.)

Continue reading “The VC Tax Break” →