Hello all, my name is Mike Konczal and I’ll be guest-blogging here this week. I want to start off with a request for comments. I think this page has one of the smarter comments sections (that statement is completely self-serving, as I am a commenter here too), and I want to get all of your opinion on a question that I’ve been thinking about lately: Where did the increase in demand for housing and subprime loans come from?

Think of our current story for the increase in subprime loans and the housing bubble: interest rates were kept too low following the attacks of 9/11 and/or there was a global savings glut. Financial deregulation allowed Wall Street to pour capital into mortgages while slicing and dicing them into investment vehicles, and politicians were happy to think the interests of Main Street (and its voters) and Wall Street (and its campaign donations) lined up perfectly. Fly-by-night unregulated subprime lenders steered borrowers into high-interest loans and/or community groups pressured banks to increase the amount of said loans, as well as restricted the increase in new houses in the most desirable areas through regulation and zoning. Alyssa Katz’s Our Lot is the best book I’ve read recently about the way deregulation and political goals worked together to get Wall Street to pour money into dubious loans.

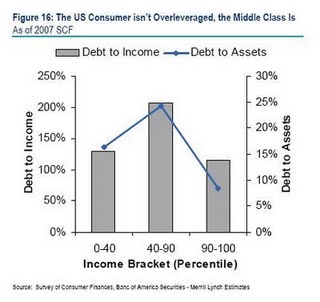

Notice that almost all of these are changes are on the supply side: Someone now wants to offer you more of a mortgage than they did before. But why did we take these mortgages? We could say that supply creates its own demand, but I think that’s too much of a dodge when there are interesting phenomenon to investigate. Here are two standard ones:

Perfectly Rational Karl Smith points out that there may not be a conflict here at all. When it comes to no-money-down liars loans, or leveraged investments more generally, the effect for consumers might be a “heads-you-win, tails-nothing-happens” coin flip. If someone offers you a giant mortgage, and the upside that your new house may become worth a lot more than the fees and interest jumps, and the downside is that you got to live in a nicer house than normal for a year or two and lost your rent, that’s a perfectly rational bet.

That’s not the experience on the ground, where people hang onto their house, fighting, often desperately at times, to keep them. Houses aren’t dumped like underperforming stocks by the overwhelming majority of consumers.

Investments Gone Bad Interest paid on a mortgage is tax deductible. In 1997, President Clinton overhauled the tax code for selling real estates; consumers would no longer have to pay capital gains taxes on their houses. Between that, the collapse of the tech bubble and the worry that there were many more Enrons and Worldcoms waiting to be found, many households didn’t want to invest in the stock market. So people went nuts and invested too heavily in housing for their investment portfolio.

(Technically, if people want to spend more on houses because interest rates are lower, then the interest rate tax deduction may have slowed the housing bubble, since if people are buying more house because interest rates are lower then they must have less interest paid on their house, which is less to write off on their taxes.)

This depends on housing prices appreciating for a long time – here’s an example of economists discussing whether or not that is rational, and trying to fold it into a standard investment story. I often feel that when the story goes too quickly into “irrationality”, it is because we are missing some sociological explanations for why people are doing the things they do. I want to add three additional reasons why the demand for housing may have skyrocketed over the past 10 years, ones I don’t see discussed very often in the standard narrative.

Housing Equity as the new Social Contract As income has become more volatile, health care costs have skyrocketed, unemployment spells have increased, more household spending has gone to hard-to-decrease fixed costs, and all the while there has been a slow unwinding of the social contract, housing equity became a new form of social insurance to navigate the bad times.

A lot of housing equity was tapped to make large consumer purchases – televisions, remodeled kitchens, etc. But a lot of housing equity was tapped to pay medical bills, or as a form of unemployment insurance, as well. It is worth noting that 60% of subprime loan defaults in Massachusetts started off as prime loans, the previously stable households who put money down, paid their bills on time, etc. I’d be curious to see research focused on how much of each played a part in the housing bubbles and demand for subprime loans, and the rise in house prices more generally.

Education There’s a lot of focus on the interest rate deduction that is embedded inside a mortgage. I think the most obvious embedded option inside a mortgage that isn’t discussed is the option to educate your children at the local school district. If sending 3 kids to a private high school at your old houses costs $5,000/year, and if the new house’s public high school is free and equally good then taking a $60,000 bath on the house is break-even. Completely rational.

The value of this option has increased, both with the returns to education but also with a general worry about the robustness of our educational meritocracy. The amount of money and energy that goes into securing access to high-end education has skyrocketed over the past decade, and part of that budget, though it isn’t treated as such, is in your house. And though we often think of educational inequality as a function of a Kozol-narrative of the poorest against the richest, this bidding may be most driven by inequality between the middle and the highest parts of the inequality curve. I’d really like to see some hard research into how much our desire to educate our children in the best way possible has driven subprime and the housing bubble.

Gentrification The term gentrification may not apply anymore, as it usually is meant to describe a small neighborhood. What we’ve seen might be described as a demographic inversion, with the poor being moved from the city to the suburbs. That New Republic article focuses on Chicago, and as a resident of Logan Square during the time in question I can back up the statement: “The reality of demographic inversion strikes me every time I return to Chicago…But that hasn’t prevented Logan Square from changing dramatically again–not over the past generation, or the past decade, but in the past five years.” Even now, with the housing recession underway, it seems that we’ll continue to see a shift to a “new urbanity” over the next ten years.

Gentrification can increase the quality-of-life for people who remain in the area. There will be better services, safer streets, the kind of grocery stores where people with college degrees shop, etc. However the key point there is that people have to remain in the neighborhood. Taking a big bet on housing can be very rational in this case. The rollercoaster jumps in mortgage payments that come from a subprime loan might be less than the uncertainty in the jumps in apartment rents that occurred over the same period.

If you were an adult in the 2000s, you’ve probably spent at least one night thinking “am I making the right housing choices? Should I buy? Should I have bought more? Less?” Since this is the smartest comments section on the nets, I’d like to ask you – why was this?