By James Kwak

While working on a new Atlantic column, I came across this article by Donald Luskin (hat tip Felix Salmon/Ben Walsh) arguing that “Taxmageddon” (the expiration of the Bush tax cuts at the end of the year) will cause the stock market to fall by 30 percent.* His argument is basically this: if the marginal tax rate on dividends increases from 15 percent to 43.4 percent, the after-tax yield falls by 33.4 percent, so stock prices should fall by about the same amount.

Ordinarily I don’t bother with faulty claims like this—there are only so many hours in the day—but it bothered me so much it cost me some sleep last night.

The first problem is the only one that Luskin acknowledges: lots of investors don’t pay taxes on dividends. He mentions pension funds; there are also non-profits and anyone with a 401(k) or IRA. According to Luskin, only about one-quarter of dividends are received by people who will pay the top rate. Maybe they are the marginal investors who set prices, he speculates. Well, maybe. But an increase in the tax rate will make dividend-paying stocks more expensive for them but the same price as before for non-taxpaying investors—so as long as we’re going to stick to theory, the former should sell their stocks to the latter for some price between the two.

More important, the price of a stock (in theory, again) is the discounted present value of its future dividend stream aggregated over an infinite horizon. So we need to know what the tax rates will be in all future years. That’s clearly unknowable. If the tax rate goes up on January 1, 2013, that will give us no information about the tax rate in 2113. On the other hand, it will give us very good information about the tax rate in 2013. And it will give us a little bit of information about the tax rate in 2023. In other words, the informational value of a change in tax rates only affects a small part of the summation you have to do if you want to value a stock by its dividend stream. If a company is going to shut down in 2013, liquidate its assets, and return one massive dividend to shareholders, it affects most of the value. If a company is Facebook and is unlikely to pay dividends for a long time, it affects very little of the value. So the impact of such a change on stock prices will be a lot less than the theoretical 33.4 percent that Luskin calculates.

Then there’s the little matter of markets. Luskin’s article chides the “stock market” for ignoring the upcoming change in tax rates on dividends. How does he know? Did he ask the market? More likely, the market is pricing in the possibility of a change in tax policy. In theory, market prices today should reflect the expected future tax level, which is somewhere between 15 percent and 43.4 percent—closer to which one, we don’t know. This is another reason why the actual impact of a tax increase will be smaller than 33.4 percent; the latter assumes that every single investor today is blindly assuming that the tax rate will remain at 15 percent. (Actually, since the Medicare surtax is already law, every single investor knows that the tax rate will be at least 18.8 percent, not 15 percent.)

But this is all theory. There is actually a way to test these things. To the extent that a change in the dividend tax rate affects stock prices, it should affect high-dividend stocks more than low-dividend stocks. Even on the theory that the value of a stock is the discounted value of its future dividend stream, for a high-dividend stock, much of that value comes from dividends in the next decade, which are likely to be affected by a change in the tax rate. By contrast, for a company that doesn’t pay dividends, the value of its dividend stream is located far out in the future, where a change in today’s tax rate has little expected impact. So if Luskin is right, the 2003 tax cut (which established the 15 percent rate for dividends) should have caused not only a sharp increase in stock prices but also a sharp increase in the price of value stocks relative to growth stocks.

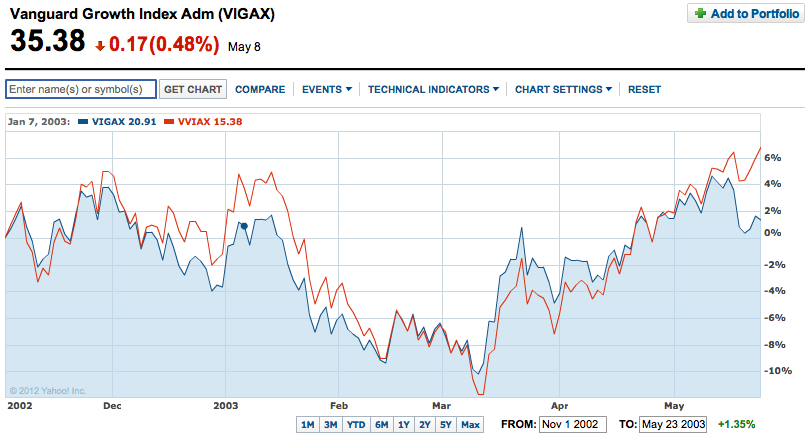

So, courtesy of Yahoo! Finance, here are the closing prices of the Vanguard Value Index (red), which includes high-dividend stocks, and the Vanguard Growth Index (blue), which includes low-dividend stocks, for November 2002 through May 23 2003, the day the final bill was passed by both houses. The question, though, is when the 2003 tax cut would have affected stock prices. There’s no separation between value and growth stocks around November 5, the day the Republicans won the midterm elections. (Remember, the Democrats had a Senate majority in 2002.) There’s none around January 28, when President Bush called for tax preferences for dividends in his State of the Union address. There’s no reaction around February 27, when the bill that would cut taxes on dividends was introduced.

Now, there is a separation around May 15, when the Senate version initially passed. (Passage in the House was assured because of the Republican majority there.) This implies that there was significant uncertainty about whether the bill would pass; when the uncertainty cleared, high-dividend stocks gained relative to low-dividend stocks. Score one for Luskin!

But if there was uncertainty that cleared on May 15, and Luskin is right, then two things should have happened: high-dividend stocks should have gained relative to low-dividend stocks, and all stock prices should have shot up. But that’s not what happened. High-dividend stocks went up; low-dividend stocks went down. Investors’ overall appetite for U.S. stocks didn’t change; at the margin, some realized that after-tax dividend yields had just gone up, so they switched from low-dividend to high-dividend stocks.

By May 23, the last date on that chart, passage was a certainty, so the impact of the tax change should have been 100 percent priced in. Do you see a 30 percent increase? I don’t.

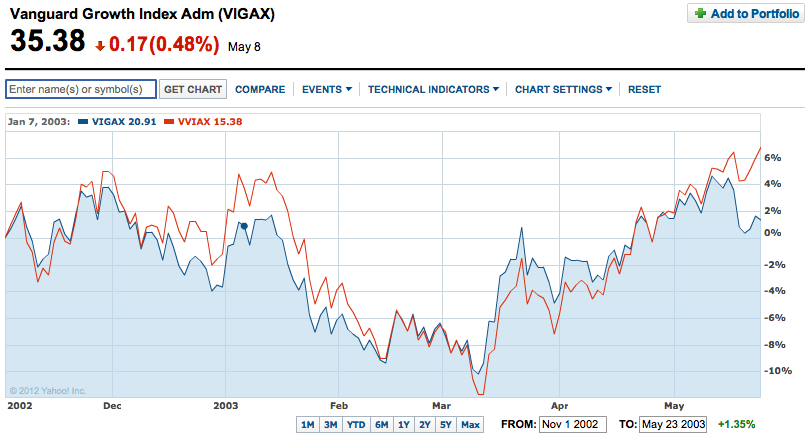

Want more evidence? Here are the same two index funds for December 1 through December 17, 2010, when the dividend tax cut was extended for two years. The extension was in serious doubt until December 6, when Democrats and Republicans reached a compromise agreement. Again, you can see an increase in the price of high-dividend stocks relative to the price of low-dividend stocks, starting around December 6. This indicates that the market was reacting to a significant change in the probability of an extension. But there’s no sharp, 30 percent increase in the overall level of stock prices.

So the tax rate on dividends does seem to have a small but visible impact on the relative price of high- and low-dividend stocks. And it may have a small impact on the overall price level, which would make sense. But 30 percent, or anything close to it, is pure fantasy.

So why all this hysteria about a collapse in the stock market on January 1? Well, here’s one hint, from Luskin’s article:

“If there’s a bargaining failure and the scheduled tax hikes on dividends aren’t stopped, we’ll be sorry we’re spending so much political energy now debating about the ‘1%’ and their supposed privileges. It’s the 30% down in the stock market we ought be worrying about.”

This is just another attempt to mask the blatant unfairness of the Bush tax cuts by arguing by arguing that that they are good for all of us (well, at least all of us who own stocks, but that’s a matter for another post). They’re not.

* Luskin also talks about “trillions more in new tax hikes under ObamaCare.” Huh? The revenue provisions of the Affordable Care Act are projected to bring in $520 billion over the next decade; even if you include the revenue-increasing coverage provisions (like the excise tax on high-cost health plans), you only get up to $813 billion. That’s not “trillions,” unless you’re talking about an undiscounted infinite horizon.