By James Kwak

These days, some papers get more attention when they are in draft form than when they are published, in part because of the length of the review and publication cycle. Recall the Romer and Romer paper on the impact of tax changes, or the Philippon and Reshef paper on the financial sector, both of which made huge splashes years before they were finally published. My best-known paper also falls in that category. “The Value of Connections in Turbulent Times” began knocking around the Internet in 2013, and is only now being published by the Journal of Financial Economics—nine years after we began working on it, and at a time when the world seems to have completely moved on from its subject. (Note: that link will allow you to download the published version of the paper for free, but only until September 4, 2016. Thanks Elsevier, I guess.)

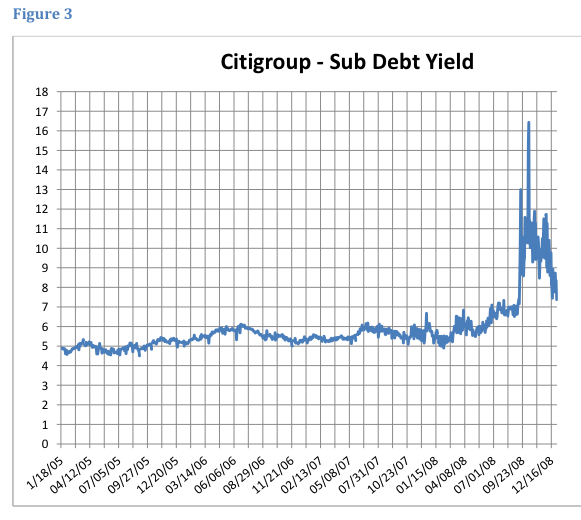

The paper, as you may have heard years back, shows that financial institutions with connections to Tim Geithner experienced abnormal positive market returns when his nomination to be treasury secretary was leaked and then announced in November 2008, and suffered abnormal negative returns when the news of his tax issues threatened to undermine his confirmation in January 2009. The interesting thing is that this is not ordinarily supposed to happen in the United States. Having connections to important government officials is not supposed to provide financial benefits to a company, and therefore nominations of those officials do not usually produce stock market bumps. The evidence is not completely one-sided, but in one representative example, researchers found that companies with connections to Dick Cheney did not experience abnormal returns in response to unexpected news about Cheney. This is in contrast to developing countries, where numerous studies have found that connections to important politicians are reflected in stock market valuations.

But it’s less clear why the markets (which, remember, are made up of at least some supposedly rational investors) thought that having connections to Geithner would pay off. Our main argument—after testing and discarding a bunch of other possibilities, like the effect was due to Citigroup, or to very large banks—is that, in the confusion of the time, it seemed likely that the treasury secretary would be given a large amount of discretion; and the more discretion that is available to an official, the more valuable it is simply to be able to get a meeting with him, or get him to return your phone call. You don’t have to think that Tim Geithner would consciously help out someone he served on a board with, or someone he had spent time with as president of the New York Fed; you just have to think that people are influenced by the people they spend time with, and so access matters.

This isn’t how we think our government is supposed to operate, but of course it’s how we all realize that it does operate. That’s one reason why individuals and corporations are willing to donate huge amounts of money to super PACs—so they can get access when they need it. What was unusual about the financial crisis was that, with the financial system and economy apparently falling apart, the value of those connections was much higher than usual. It also showed how, when push came to shove, the United States’ political institutions behaved more like those of a developing country than we would care to believe—the central point of Simon’s famous Atlantic article.