By Simon Johnson

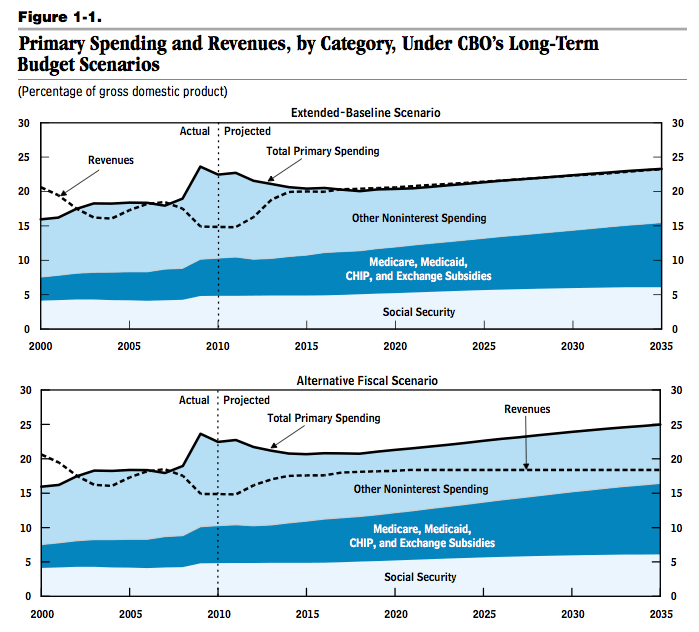

There are three views on whether the US will default on its government debts. The first is: Hopefully yes, and this August offers a good opportunity. The second is: Possibly yes, but this would be bad – so we need some form of fiscal austerity. The third is: Under no circumstances, and any talk of a need for austerity is a hoax.

The first view is mistaken. The second view hides a dangerous contradiction. And the third view borders on complacency. How can we find our way to fiscal responsibility? We need tax reform.

People in the first camp think that the US government has become too big and the only way to cut it down to size is to limit its ability to borrow. A constitutional amendment to limit the size of government relative to GDP or to require a balanced budget could work – but experience suggests there are always ways for a future Congress to escape any such constraint. Continue reading “Will The United States Default?”