By James Kwak

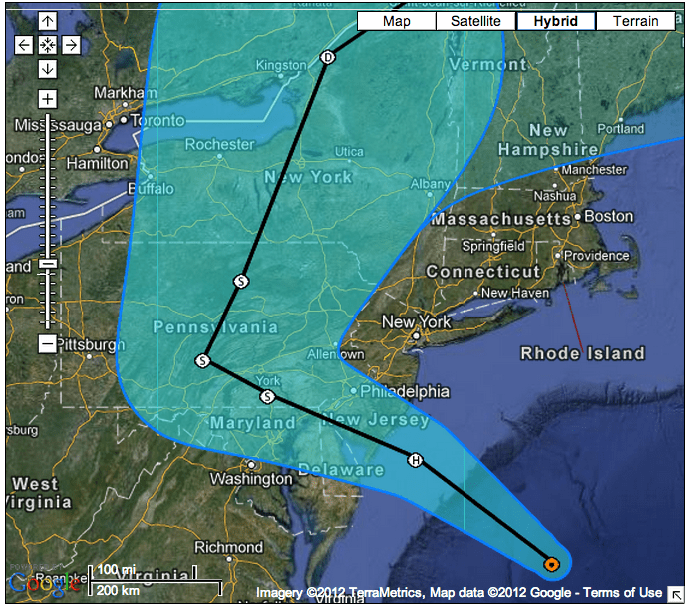

Now is as good a time as any to remind people of who provides all those detailed projections of where Hurricane Sandy is going to hit and how strong it’s going to be: the federal government. No matter how you get your weather news—local TV or radio, The Weather Channel, AccuWeather, whatever—hurricane forecast information originally comes from the National Hurricane Center, which is part of the National Weather Service. The raw data come in part from the Hurricane Hunters, the pilots who fly planes into hurricanes, who are part of the Air Force Reserve and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The computer models that predict where hurricanes are going to strike are developed by the NHC.

In August 2011, Simon and I were on vacation with our families in Southern Florida as Hurricane Irene was approaching the East Coast. Simon had the idea of using government weather services as the example to lead off chapter 4 of White House Burning, “What Does the Federal Government Do?” I like this example because almost everyone agrees that the federal government should be engaged in disaster prevention, disaster relief, and even weather forecasting. In 2005, Rick Santorum proposed a bill that would have prevented the National Weather Service from providing weather forecasts to the public—but he insisted that the NWS should gather weather data and provide it to private companies so that they could make money off of it. (AccuWeather is based in Pennsylvania, Satorum’s state, by the way.)

In August 2011, Simon and I were on vacation with our families in Southern Florida as Hurricane Irene was approaching the East Coast. Simon had the idea of using government weather services as the example to lead off chapter 4 of White House Burning, “What Does the Federal Government Do?” I like this example because almost everyone agrees that the federal government should be engaged in disaster prevention, disaster relief, and even weather forecasting. In 2005, Rick Santorum proposed a bill that would have prevented the National Weather Service from providing weather forecasts to the public—but he insisted that the NWS should gather weather data and provide it to private companies so that they could make money off of it. (AccuWeather is based in Pennsylvania, Satorum’s state, by the way.)