Last week, Ryan Grim and Arthur Delaney wrote a story for the Huffington Post about the difficulty of getting substantive reform through the House Financial Services Committee. They focus on two main things. First, because a seat on the committee is valuable for fund-raising purposes, the Democratic House leadership seems to have stacked it with vulnerable freshman and sophomore representatives from Republican-leaning districts, meaning there are a lot of Democrats who are either personally inclined to vote with the financial services industry or feel a lot of political pressure to do so. Second, a lot of committee staffers end up switching sides to work as banking industry lobbyists, and some of them then come back to be committee staffers, raising the usual questions about the revolving door. Barney Frank comes off as something of a hero; the idea is that Frank and his senior staffers are so smart and skilled that they can get effective legislation through despite the cards being stacked against them.

Month: January 2010

When a 79.9% APR Is Good?

Adam Levitin wrote an informative post on Credit Slips a couple of weeks ago; I missed it but it looks like no one in my RSS reader has mentioned it, so here goes. One provision of last year’s credit card legislation limited up-front fees to 25% of the line of credit being offered. First Premier Bank currently offers a card with a $250 credit line, $124 in up-front one-time fees, a $48 annual fee, and a $7 monthly fee. Oh, and a 9.9% APR on purchases. That adds up to $179 that gets billed immediately, and a total of $256 over the first year–more than the credit line. Because this card will become illegal in February, they are test-marketing a new card that has a $300 credit line, $75 in up-frontfees (to conform with the law; there could be a monthly fee in addition), and a 79.9% APR.

The Costs of “Extend and Pretend”

For months now, Calculated Risk has been criticizing the policy of “extend and pretend”–the practice of pretending that real estate loans are still worth their full value, making modifications so that borrowers can avoid going into default, so that banks don’t have to recognize losses on their assets. Here’s one story about “zombie buildings”–office buildings, in this case.

Alyssa Katz has a great article in The American Prospect about extend and pretend when it comes to multi-unit residential buildings, focusing on New York City. Expensive condo towers are now “see-through” buildings (so named because you see through the glass walls right through the empty floors–a phenomenon I first saw in 2001, after the Internet bust, along Highway 101 on the San Francisco Peninsula). Another problem is apartment complexes that were bought by private equity firms and flipped to developers during the boom with plans to evict the low-rent tenants and replace them with high-rent tenants; the high-rent tenants never arrived, the developers can’t make their loan payments, and no one is maintaining the buildings for the remaining tenants. (And no one is saying that property developers have a moral obligation to pay their debts rather than turn their properties over the bank.)

One of the underlying problems is that developers (or the banks that inherited their properties) have an incentive to hang on and hope for a return to prosperity that will deliver the promised condo buyers or high-rent tenants–in other words, betting on another boom. The alternative is selling the properties to someone who will convert or restore them to the type of housing that there is actually demand for–affordable rental units–but that means that someone has to take a loss, because an affordable building is simply worth less than one stuffed with investment bankers. Unfortunately, as Katz says, “With so many lenders at the brink of insolvency, the Treasury Department and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) appear to be in no rush to cause them further pain.” The lack of urgency was unwittingly confirmed by a Treasury spokesperson, who said, “The commercial real-estate market is something we’re watching closely, but it’s premature to discuss solutions.”

By James Kwak

Countdown to January 18: Goldman’s Bonus Day

Sources say that Goldman Sachs’ bonuses will be announced on Monday, January 18, and actually paid sometime between February 4 and February 7. In previous years, the bonuses were paid in early January – but the financial year shifted when Goldman became a bank holding company.

For critics of the company and its fellow travelers, the timing could not be better.

Anxiety levels about the financial sector are on the increase, even on Capitol Hill. The tension between high profits in banking and stress in the rest of the economy becomes increasingly a topic of discussion across the nation.

And you are hard pressed to find any government official who has not by now woken up – in private – to the dangerous hubris of big banks. To add insult to injury (and many other insults), the Bank for International Settlements is holding a meeting to discuss excessive risk-taking in the financial sector; according to CNBC Thursday morning, Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman and Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase were invited but did not show up (they really are very busy).

The smart strategy for Goldman in this context would be to pay no bonus for 2009 (in cash, stock or any other form), but this is not possible for three reasons. Continue reading “Countdown to January 18: Goldman’s Bonus Day”

Bankers and Athletes

Bill George, a director of Goldman Sachs, defending the bank’s compensation practices, said this: “The shareholder value is made up in people and you need the people there to do the job. If you don’t pay them for their performance, you’ll lose them. It’s much like professional athletes and movie stars.”

The idea that the level of inborn talent, hard work, dedication, and intelligence you need to be a banker is even remotely comparable to that of, say, NBA basketball players is ridiculous. But leaving aside the scale, there are some similarities. Most obviously, athletes on the free market–those eligible for free agency–are overpaid. John Vrooman in “The Baseball Players’ Labor Market Reconsidered” (JSTOR access required) goes over the basic reasons, but they should be familiar to any sports fan. There is the lemons problem made famous by George Akerlof: if a team gives up a player to the free agent market, it probably has a reason for doing so. There is the winner’s curse common to all auctions: estimates of the value of players follow some distribution around the actual value, and the person who is willing to bid the most is probably making a mistake on the high side.

Good Idea Coming

One striking aspect of the public debate about the future of derivatives – and how best to regulate them – is that almost all the available experts work for one of the major broker-dealers.

There are a couple of prominent and credible voices among people who used to work in the industry, including Frank Partnoy and Satyajit Das. And there are a number of top academics, but if they help run trading operations they are often unwilling to go on-the-record and if they don’t trade, they lack legitimacy on Capitol Hill and in the media.

The Obama administration is criticized from various angles – including by me and, even more pointedly, by Matt Taibbi – for employing so many people from the finance sector in prominent policy positions. But, the administration pushes back: Where else can we find people with sufficient expertise? Continue reading “Good Idea Coming”

The Problem with Positive Thinking

There’ s a quotation by Stan O’Neal that I’ve looked for occasionally and failed to find. John Cassidy found it for me (How Markets Fail, p. 274; original source is The New York Times). It was an internal memo from O’Neal describing the company’s second-quarter 2007 results (which were good, at least on paper). Here are some quotations from memo in the Times article:

“More than anything else, the quarter reflected the benefits of a simple but critical fact: we go about managing risk and market activity every day at this company. It’s what our clients pay us to do, and as you all know, we’re pretty good at it.”

“Over the last six months, we have worked successfully to position ourselves for a more difficult market for C.D.O.’s and been proactively executing market strategies to significantly reduce our risk exposure.”

Greg Zuckerman, in The Greatest Trade Ever, has this from O’Neal in 2005 (p. 173): “We’ve got the right people in place as well as good risk management and controls.” (No original source–the entire book has only forty-three end notes, at least in the pre-publication copy that Simon got.)

Hoenig Talks Sense On Casino Banks

Thomas Hoenig, President of the Kansas City Fed, has been talking sense for a long time about the dangers posed by “too big to fail” banks. On Tuesday, he went a step further: “Beginning to break them, to dismember them, is a fair thing to consider.”

Hoenig joins the ranks of highly respected policymakers pushing for priority action on TBTF, including some combination of size reduction and/or Glass-Steagall type separation of casino banks and boring banks.

As Paul Volcker continues to hammer home his points, more policymakers will come on board. Mervyn King – one of the most respected central bankers in the world – moves global technocratic opinion. Smart people on Capitol Hill begin to understand that this is an issue that can win or lose elections. Continue reading “Hoenig Talks Sense On Casino Banks”

Still No To Bernanke

We first expressed our opposition to the reconfirmation of Ben Bernanke as chairman of the Fed on December 24th and again here on Sunday. Since then a wide range of smart economists have argued – at the American Economic Association meetings in Atlanta – that Bernanke should be allowed to stay on.

I’ve heard at least six distinct points. None of them are convincing.

- Bernanke is a great academic. True, but not relevant to the question at hand.

- Bernanke ran an inspired rescue operation for the US financial system from September 2008. Also true, but this is not now the issue we face. We’re looking for someone who can clean up and reform the system – not someone to bail it out further. Continue reading “Still No To Bernanke”

Did Demand for Credit Really Fall?

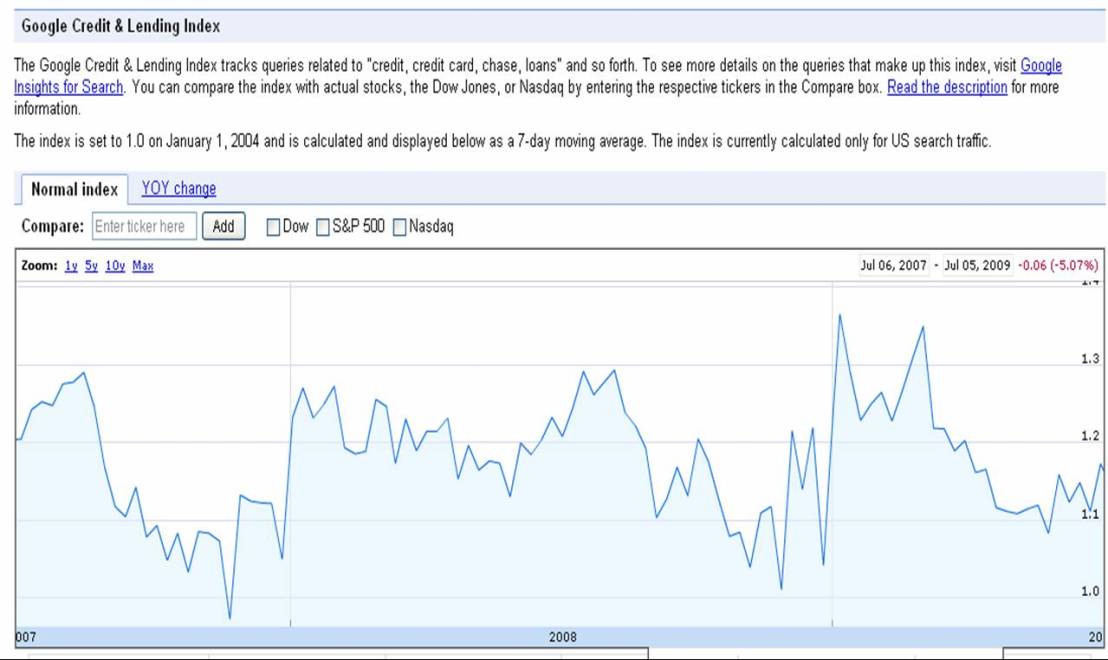

One standard attack against banks is that they have not expanded lending sufficiently to help the economy recover. The standard defense has been that the supply of credit collapsed only in response to a collapse in the demand for credit. The primary measure of demand for credit that I know of is the one compiled by the Federal Reserve by surveying bank lending officers; it shows falling demand for all types of credit from 2006, with an acceleration in the fall in late 2008.

Presumably this is based on the number of people walking into bank branch offices (or calling up on the phone, or applying online, etc.). But Google has another way of tracking demand for credit; the Google Credit & Lending Index measures the relative volume of searches* for certain terms like “credit card,” “loan,” and “credit report.” There’s some seasonality there, but in general the levels look higher in Q4 2008 and Q1 2009 than in Q4 2007 and Q1 2008.

“All Serious Economists Agree”

The most remarkable statement I heard at the American Economics Association meeting over the past few days came from an astute observer – not an economist, but someone whose job involves talking daily to leading economists, politicians, and financial industry professionals.

He claims “all serious economists agree” that Too Big To Fail banks are a huge problem that must be addressed with some urgency.

He also emphasized that politicians are completely unwilling to take on this issue. On this point, I agree – but is there really such unanimity among economists? Continue reading ““All Serious Economists Agree””

Bye-Bye, Bank of America

As I was waiting for the very nice bank teller to give me my bank check for the balance in my account, the woman next to me was trying to tell her very nice teller that she did not want overdraft protection on her account. She was told she would have to wait fifteen minutes to talk to a “personal banker” to remove it. Weren’t big banks supposed to be more efficient?

My nice “personal banker” made the mistake of asking me why I was closing my account. So I told him:

- One of my local banks refunds my ATM fees at other banks.

- My other local bank pays 0.75% interest–on an ordinary checking account.

- Bank of America breaks the law.

- Bank of America closed two out of the three branches in my town.

- Oh, and it’s too big, and presents a systemic risk to the U.S. economy.

Behind him was a sign encouraging people to use their debit cards to pay for purchases to take advantage of a “savings” program that moves what is already your own money from your checking account to your savings account.

Afterward I went out for a martini even though it was just before noon. Yes, changing your bank account is a hassle. But the satisfaction is worth it.

By James Kwak

Yet More Financial Innovation

Andrew Martin has an article in The New York Times on the dynamics of the debit card industry. I don’t have any expert knowledge to add, but here’s the summary: Visa has been increasing its market share by increasing the prices it charges to merchants; it takes those higher transaction fees and passes some of them on to banks that issue Visa debit cards, giving them an incentive to promote Visa debit cards over other forms of debit cards. Not only that, there are different fees on debit cards depending on whether you use them like a credit card (signing for them) or like an ATM card (entering a PIN). Signing costs the merchant more, so the banks and Visa give you incentives to sign instead of using a PIN. The end result is higher costs for merchants, who pass them on to you.

The Crisis This Time

This morning at the American Economic Association (AEA) meeting in Atlanta, I was on a panel, “Global Financial Crises: Past, Present, and Future,” with Allen Sinai (the organizer), Mike Intriligator, and Joe Stiglitz.

The Wall Street Journal’s RealTime ran a summary of my main points: growth in 2010 may be faster or slower – depending on how lucky we get- but, either way, the most serious problem we face is that 6 banks in the U.S. are now undeniably (in their own minds) Too Big To Fail. Continue reading “The Crisis This Time”

Another Approach to Compensation

The problems with the traditional model of banker compensation are well known. To simplify, if a trader (or CEO) is paid a year-end cash bonus based on his performance that year (such as a percentage of profits generated), he will have an incentive to take excess risks because the payout structure is asymmetric; the bonus can’t be negative. That way the trader/CEO gets the upside and the downside is shifted onto shareholders, creditors, or the government.

I was talking to Simon this weekend and he said, “Why a year? Why is compensation based just on what you did the last year? That seems arbitrary.” When I asked him what he would use instead, he said, “A decade,” so I thought he was just being silly. But on reflection I think there’s something there.