This guest post was contributed by StatsGuy, a regular commenter on this blog.

In the current healthcare debate, Conservatives warn us that a single payer system will bring government rationing… Progressives argue that we already have rationing, based on wealth. Both sides are right, but both pretend that rationing is bad. Yet as every economist knows, the allocation of scarce resources is the basis of economics itself. The question is not whether we will have rationing – the question is how to structure a system of rationing that accomplishes our goals.

Two primary themes dominate this debate:

The Uninsured: In the past two decades, both the total number and the percentage of uninsured have increased in spite of some modest programs designed to expand coverage (like CHIP). (Original chart is here.)

The graph above, which extends through 2007, has surely worsened since 57% of US citizens are insured through their workplace (down from 63% in 2000) and unemployment increased from under 5% to 9.4% in the last couple years.

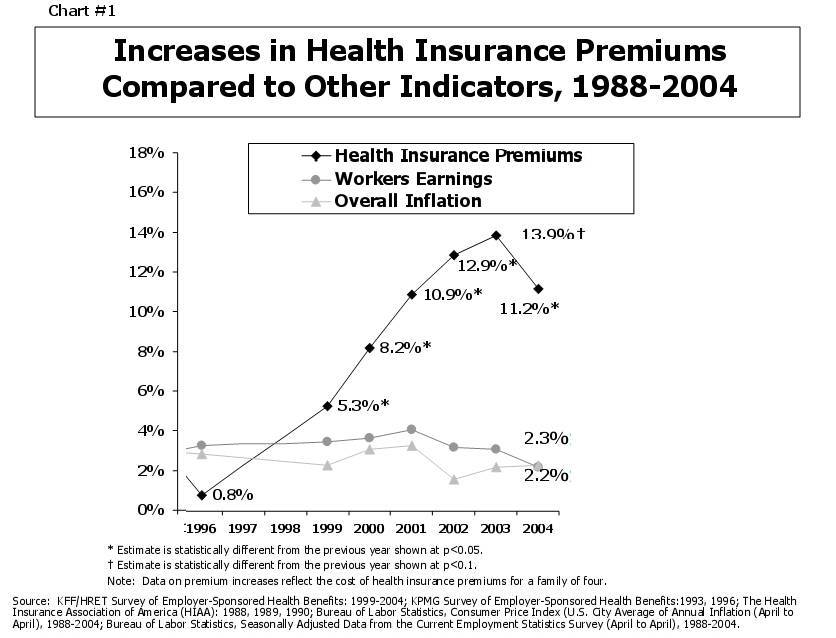

Rising Costs: During the same time, costs have increased dramatically. (Original chart is here.)

Part of this is because of the availability of new treatments and technology in the last 20 years… Part of this is because the population in the US suffers greater morbidity than 20 years ago. But much of the increase is due to systemic issues caused by gross market failures in the healthcare market, as described by Baseline here and elsewhere.

However, costs and coverage interact. Businesses (especially smaller ones) drop insurance because they cannot afford premiums. On the other side, lack of coverage drives up costs… The uninsured may overuse emergency room care, delay basic care until a disease worsens or fail to get vaccinated (which harms themselves and others). At the systemic level, administrative costs (which largely consist of managing payments and coverage) are growing much faster than overall costs.

So what can we do?

1) Fix the broken incentives

The current systems for federal and private reimbursement of health care expenses (via Medicare and Medicaid) are rate of return systems – a type of cost-plus regulation. In other words, health care providers are reimbursed for the quantity of care provided. The more they provide, the more they are reimbursed. Only HMOs do not compensate through this structure, and they have been credited with holding down costs vis-à-vis PPOs. (Moreover, they are now equaling or exceeding PPOs on other dimensions than cost.)

Even worse, the reimbursement schedule in existing government programs is broken; Medicare compensates primary care services at rates that are often below costs (which have increased faster than inflation adjustments), while richly compensating certain medications (because the govt. is banned from negotiating prices) and equipment intensive procedures (which have decreased relative to inflation in the same way that microchips have gotten cheaper). We have a vast amount of data that tells us that primary physician care is far more cost effective than treatment by teams of specialists, but the current rate schedule contributes to a substantial undersupply of primary care physicians that is likely to get worse as we see substantial year-on-year declines in the percentage of new graduates entering family medicine. Previous government reports suggesting that everything is fine contradict what many doctors are saying.

The best of the current proposals (the House bill, with summary here) does take steps to restructure rates, but needs to do more. We need to increase reimbursement for basic care, reduce reimbursement for the most expensive care, and set up a rational system for updating fee structures. New legislation should:

- Create an independent, self-funded agency with rate setting authority.

- Establish a set of advisory commissions to recommend rates and coverage using evidence-based analysis; commissions should be primarily staffed by doctors (with minimal conflicts of interest) that balance across regions, private practice, hospital staff, etc. Primary care providers should be well represented. Patients rights, public interest, and budget-watching public interest groups should also be represented.

- Mandate rates that adjust for cost-of-service by region; uniform national incentives encourage over-treatment in low cost regions and under-treatment in high cost regions.

- Shift away from a model that compensates purely based on quantity of care. We need a system that rewards cost-effective care (i.e. quality care that is worth the price). What might such a system look like?

In the 1990s, HMOs experimented with capitation – rewarding doctors based on number of patients they managed rather than services. Unfortunately, this incented doctors to under-treat and also to avoid taking on unhealthy patients. To address this, we should deploy a hybrid system that rewards primary care doctors partly based on services they provide (with rates determined as noted above), and partly based on a risk-adjusted capitation model. The fee-portion of the system would ensure that doctors do not lose money on patients that require more treatment than anticipated, but would not drive profits. That way, doctors have less incentive to insist patients come in for an office visit when an email would suffice. The risk-adjusted capitation portion of their compensation would pay providers based on the morbidity of the patients they enrolled (with sicker patients generating more income since they take more time to manage). Electronic records would enable us to measure provider performance based on outcomes. Properly balanced, this would help minimize both the incentives to over treat and the incentives to under treat.

2) Focus coverage-enhancing proposals on cost-effective basic care:

Current proposals that dramatically expand coverage without focusing on cost containment (like the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee version) had hoped to pay for themselves through efficiency enhancement. The notion was simply this: if we can improve preventative care, lower administrative costs, and teach doctors that better care is not always more care, then consumption will decline by itself. This optimistic view hit a roadblock when the CBO estimated that these proposals would not achieve their cost reduction targets due to insufficient incentives to reduce consumption. The CBO analysis may be pessimistic, but is not easily dismissed.

As an alternative to providing the best care to everyone, an efficiency-focused regime could focus on expanding cost-effective basic coverage for everyone, and allow individuals to purchase supplemental coverage at their own expense. This enables those who want more care to buy more care (wealth permitting); those who cannot afford to buy private supplemental insurance would be subject to government rationing.

Extending cost-effective basic care to everyone would lower costs associated with overuse of emergency rooms, administrative billing, public health issues (like failure to vaccinate), etc. While not overly generous, it could offer a basic social safety net, and for reasons that Baseline has covered, it makes a great deal of sense for a Public Option to exist that covers cost-effective basic care.

Private supplemental insurance would need to be well regulated. In particular, rescission should be banned outright (which would front load application costs), or tightly regulated and managed by accelerated legal review (a 6 month legal delay for a chronically ill person will create serious distortions).

Denial of coverage due to pre-existing conditions must be addressed, but not by simply banning it. Insurance companies will attempt to evade the regulation – for example, by deploying marketing campaigns that target healthy individuals and avoid unhealthy ones (should they advertise in Cycling magazine, or Coping with Cancer?). If we want to subsidize care for people with pre-existing conditions we should do so directly, rather than shifting the burden to insurance companies and pretending we aren’t paying it. Indeed, we’ll end up paying more as insurers spend money on rent-seeking activities to cherry pick patients.

3) Infrastructure

The current proposals do a decent job at expanding infrastructure, so I will limit comments to:

- The scarcity of general care physicians is a structural issue that will take time to respond to new incentives. Until this balance is restored, the federal government should provide tuition support (via loan forgiveness) for medical students that enter primary care and remain in primary care for at least 10 years (10% loan forgiveness per year).

- More needs to be done on malpractice insurance. Many factions argue the root problem is growth in tort awards. And in the long term the correlation is clear, but since the tort reform movement in 2001 insurance company payouts have actually declined in real dollars, even as rates have spiked by 120% so that the payout ratio is now less than 45%. (also, here) The problem now seems to be the insurance companies more than the lawyers.

- We should do more in meeting standards for physical hospital infrastructure and best-practice dissemination that reflect our current state-of-knowledge; this is a public health concern. These types of efforts can have a huge payback.

- The current proposals hit the mark on building a nationwide electronic system for managing patient records, and the CBO review does not give full credit to this initiative. While the administrative savings would be substantial, the greater value is in knowing what actually works, what is a waste of money, where the problems are, and which providers are performing well. Imagine monitoring the H1N1 flu in real time. Comparing the efficacy of treatments and drugs with statistically robust samples of hundreds of thousands of patients. Measuring whether costly new procedures yield better outcomes. Tracking drug interactions. Monitoring whether hospitals are following best practices at infection control. The decentralization of information that usually helps a free market system work so well is working against us in health care.

In conclusion…

Some of the proposals in Congress that focus primarily on expanding coverage (especially the Senate HELP committee version) are likely to incur massive costs by subsidizing the growth of a system with underlying structural problems. This is precisely the same critique that Baseline has leveled against the currently weak proposals to fix regulation in the financial system. The House bill does much better (which CBO acknowledges), but should do more. The painful truth is that if we are going to seriously keep health care costs from destroying our federal budget, we are going to need to accept rationing. Unless the political will suddenly emerges to move wholesale to a Canadian system of rationing, health care reform may have a better chance of success by fixing the broken incentive system, focusing public subsidies on cost-effective basic care, and augmenting infrastructure.

By StatsGuy

I would to this just add two concerns

First whatever you do, don’t let the Basel Committee be involved. They would just empower health rating agencies to check up on the citizens and thereafter place some special capital requirements on the insurances of the unhealthy; by which they can provide a very fiscally sustainable and Darwinian solution to the whole problem.

Second as a foreigner I am shocked at how the health sector is allowed to charge the uninsured with prices for services and medicines that are several times higher than what they are paid by insurance companies. One prize independent of whether insured or not should be the rule… and I say that, on its own, could take care of a lot of problems.

By the way this is a great post. Of course there is always some rationing going on… don’t we have SATs and GMATs and what have you for that?

This is all very good, but as TippyGolden remarked earlier, why go through these contortions to preserve the profits of private insurers?

I should be more emphatic: this is the best most balanced summary going for how to improve things without switching to single-payer.

Another thing I’d like to emphasize from what you’ve pointed out is the use of information systems to fine tune things like incentives.

Very good post. They hybrid payment system mentioned is what is contemplated under the accountable care organization (ACO) concept that has been the focus of payment reform advocates lately.

How one deals with adverse selection into enhanced (supplemental) plans is a key issue not addressed here. There are solutions but I don’t know if they’re all palatable (e.g. risk-adjusted premiums).

Benefits of electronic health records are real but are a long way off. Interoperability is a key problem. Likely we’ll go through a period during which systems don’t communicate with one-another well. Much later things will improve, if incentives are right.

By “the House bill” I presume you mean H.R. 3200 and not H.R. 676, and why you think that huge, cumbersome jumble marred by legislative medical practice without license is “the best” is more than I can fathom.

Have you looked at anything written by Steffie Woolhandler or her colleagues at Physicians for a National Health Program (www.pnhp.org)? Might it not be prudent to consider the views of people who both practice medicine and study the economic and public health consequences of different types of funding? Not heeding their advice is the classic business blunder of instituting a new system without consulting those who have to use it. In an ordinary office, that means a lot of overtime and angry customers; in national health care it means a lot of dead people.

Very good post.

I would point out that a major reason that malpractice premiums rose in recent years was the insurance companies poor return on investments.

This is why it needs to be done under the rubric of the Semantic Web.

Single payer would SAVE money and lives; just not private insurance company profits. Let’s be clear about what we are trying to save here.

We need a system that rewards cost-effective care (i.e. quality care that is worth the price). What might such a system look like?

How about taking “customer satisfaction surveys” and paying a bonus to those doctors who receive high marks from their patients? Satisfaction with care and quality of care may not be precisely equivalent, but I bet they are darn close. So if you want to reward quality, reward customer satisfaction.

…

Alternatively, just give people health care vouchers…

In order for that system to work well, everyone would need sufficient medical education to be able to decide when to be satisfied or not. They would also need to be even-tempered and fair. First, do that, then we’ll talk about customer satisfaction surveys.

First off, systems that reward cost-effective care have been tried. When Kaiser-Permanente first invented the HMO, that was their plan for how these were going to be popular and affordable: get people into preventative care, and when that fails, treat early while it’s still cheap. It didn’t work, because even if you make it free, Americans wait too long to go to the doctor, waiting until they’re already really sick.

You say that a basic purpose of economics is to allocate scarce resources, but for crying out loud, why IS health care a scarce resource? Why can’t we do what several other countries have done, and simply massively increase the number of students we admit to medical school and to dental school? We already turn away more qualified applicants than we admit every year.

Maybe if we had twice as many doctors and twice as many dentists, people wouldn’t wait until the last minute to go, because there’d be enough doctors that non-emergency care didn’t require a 7 to 10 working day wait. Maybe if we had twice as many doctors and twice as many dentists, we wouldn’t have to argue about whether we’re better off letting insurance companies ration access to doctors or if we’d instead be better off having government agencies ration the access to doctors.

Of course, if we did this, doctors’ and dentists’ salaries would, as they have in other countries, drop to the comfortable middle-class living range instead of the lower end of wealthy. Which is why the AMA and the ADA have been fighting hard to keep states from expanding their medical schools ever since the 1970s, and will continue to do so forever. They’re not your union, as a patient, they’re your doctor’s union. And they’re the only unions left in America that are still politically powerful, with both political parties, that they get to dictate to the public the level of competition they’re willing to put up with, why they’re the only workers in America still powerful enough to dictate their salaries to us instead of negotiating for them in a free marketplace.

Some doctor or dentist or medical student will almost certainly reply that if we didn’t restrict the number of doctors and dentists, cut throat competition would drop their wages to the point where qualified people would refuse to go to medical school. I will answer this objection in advance: where’s your evidence for this? Not anecdotal evidence of whether or not you’d refuse to, for example, fix teeth if it paid only $99k/yr instead of $169k/yr, but your evidence that even if you did choose a different profession, there wouldn’t be two equally qualified applicants eager to do the job for $99k/yr, or even for less? Show me one country that’s facing a shortage of doctors or dentists because they don’t pay enough before you assert that allowing additional competition in the medical practice business would be bad.

Brilliant post !!!

Absolutely correct. No private provider can escape the conflict of interest between the needs of doctors and patients and the desire of investors to see ever-increasing profits.

Another frequently voiced objection is that unless they are paid twice as much as everyone else in America, they will never pay off their student loans. Always some joker of a doctor will write in and say it’s now 20 years after medical school graduation and he still has student loans (the he has been postponing paying off). A very easy solution for this is loan forgiveness for those who have student loans in medicine, and a lowering of medical school tuition rates so that all accepted applicants can easily afford it.

Another group of doctors will write in and say they make $75,000 a year already and any pay cut will make it more attractive to teach kindergarten. Yes, there are some doctors with reasonable salaries, but this is totally atypical. However, since managed care came into being doctors traditional pay has taken a beating. Who is skimming the payola off of doctors’ salaries? The insurance industry.

Another reason it’s a scarce resource is because devicemakers and pharma charge too much and artificially limit the number of their devices. After all, these devices can be made on an assembly line using a combination of human and robotic labor.

Also, there is a huge contingent of doctors who went into the field for the money or the prestige of having the money. I cringe whenever I imagine what they told their medical school interviewer. These people are not going to give up what they’ve worked so hard for without a fight.

On the contrary, it only requires that most people, on average, know when they are feeling sick and when they are feeling better.

I know, I know, most people are too stupid to figure that out for themselves and need a bunch of brilliant altruistic government bureaucrats to tell them.

All terrific and true. And all very rationale, which is why it needs a followup post on how to make it visceral and emotion laden.

The discussion needs to switch to a political sphere to make messages that resonate with people that do not understand the details, and in a representative Democracy, maybe shouldn’t have to be health care wonks.

This addresses a big part of the problem. Another factor is that only individual citizens acting responsibly one by one are really competent to manage their individual ‘health care’, and far too many refuse to do it. Every top down solution, regardless of how ingenius it may seem, can ultimately be gamed by providers mongering fear and overtreating with drugs and expensive technologies a herd of sheep unwilling to take the smallest responsibility for either managing their own health or acquiring independent knowledge when anything starts to go wrong. When you load on top an ‘insurance’ sector which has captured balkanized state regulation as ours has, the result is an industry that threatens to bankrupt us even more quickly than the arms race of recent memory very nearly did. I agree that increasing the supply of physicians could certainly help. It is pretty much a fantasy to expect us to gain any control over costs without some kind of government option that cuts dramatically into insurance and drug company profits.

Great post. (Hate the headline!)

Was talking to my ped the other day – he wants reform, though is not happy with what he’s seeing. Issues his practice is facing:

– in a downturn like this, lack of insurance means people are less likely to come – this particular practice has taken a big hit in the last year.

– If you take Medicaid patients, your reimbursement is subject to the vagaries of state government – and those payments are six months or more late – the state is asking these practices to essentially subsidize the treatment for at least a half a year.

– Medicare/Medicaid rates are significantly lower than private rates, so costs are indeed passed on to private rates. When we look to Medicare as “THE system” to follow, we need to recognize that the lower government rates are subsidized by the much higher private rates charged to those with health insurance.

I differ from StatsGuy on a key issue – rescission – I think it needs to be banned outright. If we are to subsidize treatment for patients who would be considered for rescission, instead of banning it outright, we’re actually institutionalizing even greater profits for health insurance companies. We’re saying that they can continue to take money from healthy patients, but once they’re sick, the government will help pick up the tab. (If you meant something different, please elaborate!)

That happens now, but once it becomes a regulatory standard, it will be a bonanza for insurance companies.

We’re seeing less and less family care/pediatric physicians because they’re getting hammered on the reimbursement side, while those in specialty medicines are increasingly well rewarded. If we really want “health care” instead of “disease treatment” the way we reimburse family practice physicians will need to be adjusted. The way we pay for all treatment will need to be adjusted. Not seeing that addressed in the bills…. but haven’t had the time to pore through all the many new regulations proposed.

Please look up rationing in any dictionary, then open any economics textbook. “Rationing by price” can only occur in a market where supply is fixed. Use of this term suggests basic ignorance, intellectual stubbornness, or a decision to abuse the English language to political ends. Stop it. [By the way, I don’t disagree with most of your recommendations.]

This is not about people being stupid, Nemo.

Some people just want to feel like something is being done. Of course, sometimes, something doesn’t need to be done, and the doctor who does nothing in this case will get penalized.

Also, whether you feel good or bad is often not related to the efficacy of your care. And individual doctors don’t treat enough people for us to be running statistical surveys about how they feel anyway.

And a couple points about vouchers. First, they cannot absolve healthy people from the responsibility to pay into the system, if you want universal coverage. Universal coverage cannot work without healthy people paying more than their share. If you want to give them vouchers while still requiring them to pay, then fine, but it seems a rather contorted way of doing it.

Secondly, vouchers assume that patients can adequately assess their health situation and won’t put off preventative treatment or avoid getting help when they should, and they also assume that patients will save the voucher money and not burden society when they are broke and sick later.

These are a couple of big assumptions.

I understand the appeal of vouchers. They are an attempt to address the difficult issue of figuring out how much care is too much and how much is too little. Vouchers try to enlist the patient in this role.

Unfortunately, while patients generally have the right motives under a voucher system (stay healthy, pay less), they are often not equipped to make the kind of informed decisions that are needed.

This health care thing is hard stuff, Nemo. Reflexively seeking out “private” solutions for a public problem will only limit our options. Let’s consider everything.

I agree it is hard stuff, and I am not “reflexively” seeking anything.

Health care is fundamentally hard because it involves decisions about who lives and who dies. We do not have the resources to save everyone. Or, if you prefer, we do not have the resources to prolong everyone’s life indefinitely. To even approach mentioning this fact is political suicide; witness the hullabaloo about “death panels”.

So the question is, whom do we sacrifice and whom do we save? Realistically, our choices boil down to two: Save the rich and sacrifice the poor (private system), or save the politically well-connected and sacrifice the less well-connected (public system).

Decisions, decisions…

I read the linked article about the low payments to primary care physicians (http://www.cnn.com/2009/HEALTH/08/25/harris.primary.care.doctor/index.html), and am now confused about why health care costs are spiraling out of control.

Is the argument for reform that Medicare is paying too much to specialists and not enough to primary care physicians, who can help prevent catastrophic health problems (thereby reducing the number of specialist treatments required)?

As for the student loan issue, if there were twice as many med-school openings, then maybe tuition wouldn’t be bid quite so high at them, either, would it? Would they still have the same “oh my student loans” complaint if med school cost half of what it does?

Once again, we’re bumping into the problem of how to ration a scarce resource, when the reasons that it’s scarce are all entirely artificial. There is no natural scarcity of health care. There is no shortage of people who could be trained to provide it. There is no shortage of places to put hospitals and clinics; in fact, most cities have mothballed hospitals they shut down years ago to, you guessed it, reduce competition. The raw materials the drugs and devices are made out of are all common. The only scarcity there is in health care is scarcity that’s enforced by America’s single most successful price-fixing cartels, the AMA and the ADA.

J. Brad,

Great post. Injecting competition into the healthcare system is a must. BTW, just a few decades ago, a college degree did not cost the enormous amount of money it does now. Many of the problems that have put the squeeze on consumers are reflected in the way our college system cost structure has spiraled out of control. It would be much cheaper just to subsidize medical students so the high costs of earning that medical degree would be significantly lessened.

But the key point of your post is that medical care need not be a scarce resource, and it need not be rationed. There are ways to reduce cost without rationing to the point where the government is picking who lives and who dies. The plain fact is that our present healthcare system is one where influential parties, the AMA, our University system, the Trial Lawyers and our government to name just four, have skewed market forces in ways that have driven up cost dramatically.

Well then, if the supply is not fixed, why are the prices so high? Shouldn’t they be very low?

The answer is that the supply is artificially fixed by rent-seekers through artificially high prices and barriers to entry (a comment above mentioned the way medical education limits entry; I add barriers vs. immigration and certification of foreign doctors who might be willing to work for less).

Ergo rationing by price.

I hope we don’t import too many immigrant healthcare providers. We decimate the local healthcare capacity of developing countries by doing this.

Let me quote myself from my “Voice and Noise” of 2006

Solving the shortage of caretakers

An older population, many of whom will experience longer periods of chronic illness and dependency before dying will require a growing number of caretakers. If there are enough caretakers, the issue will be to find the resources to compensate them. However, if there are not enough trained caretakers, no financial resources would suffice, and you have to find practical solutions.

The practical solutions available for solving the shortage of caretakers in developed countries are the following four:

1.Increase their productivity, but unless you wish to run the risk of being dehumanized on a Charlie Chaplin Modern Times assembly line cared for by robots… there might be a limit to how much this can help.

2.Move the careneeders to another place (if there are caretakers available anywhere else), and this you should do as early as possible if at an older age you do not appreciate finding yourself in strange surroundings as much as you did when younger.

3.Import caretakers, and this you should do as early as possible if when older you do not appreciate finding yourself in the company of strangers as much as you did when younger.

4. Give incentives for having more children and grandchildren—which is not such a crazy idea when you start considering how much society is, one way or another, currently rewarding people for not having children. (Talk about externalities!)

The Presidents Council of Bioethics http://www.bioethics.gov (USA) published in September 2005 its report titled “Taking Care”. It makes all types of thoughtful recommendations about the issue of Ethical Caregiving in Our Aging Society. As much I appreciate its effort, I do not think that the report spells out sufficiently the need for much more forceful and immediate work on achieving practical solutions. If those solutions are not found, the frontiers of what is currently considered ethical caretaking will just have to move to take up for the slack. No matter how horrendous it sounds, euthanasia and other flexibilities needed to bridge intergenerational conflicts might then turn out to be thought of as the only ethical solutions to the problems. In this respect, the most clear and real unethical behavior today is that of not anticipating and providing timely solutions.

As a practical matter, if the foreign doctors won’t come to us, we go to them…in droves…whenever possible. Medical Tourism is booming because of the vast amounts of money that can be saved for essentially the same (and often better) services.

Anyone who gets sick in the U.S. in a non-emergency situation and who is well enough to travel should probably seek medical care in another country to avoid going into bankruptcy.

Per you must enjoy saying “I told you so”, since the U.S. government has never looked more than a quarter ahead.

Excellent post

Sorry it is not only the government.

Also the conservative, progressive and of course middle of the road think-tanks. http://bit.ly/174NQC

I understand what you mean about risk taking, but we also need to consider the payoff from the risk: is it even something socially desirable?

umm…I realize you point that out, but I wanted to emphasize that point: the payoff from successful risk taking must benefit society. When you lend to sociopaths to take risks, you get chaos when they are successful.

Absolutely! As I have said many times, in the long Basle Epistles there is not one single word about the purpose of the financial sector… all is about avoiding the regulators’ monsters.

Nemo, I think you’re way off base here.

I could give you a long wonkish litany of the technical reasons that customer satisfaction surveys are a terrible way to measure quality of health care. But let me share with you, instead, two anecdotes that I think illustrate (but do not prove) my point clearly.

Back in the 1980’s, I encountered in my medical practice some patients who had been treated by a colleague who was, in other ways, starting to show signs of senile dementia but continued to practice medicine. Some of these patients had been treated in rather bizarre and dangerous ways, often for diagnoses that could not be substantiated. Ultimately, our hospital’s Department did an audit of his care and we learned that he was giving cancer chemotherapy–which has life-threatening side effects–to patients who didn’t even have any cancer. One of those patients died as a direct consequence of those treatments. But let me tell you, I never met a doc whose patients loved him more. They were the most satisfied customers in the world.

The other anecdote concerns a familiar figure, with whom I have no personal acquaintance at all: former Senator and Presidential Candidate Bob Dole. You may recall that after his political career ended he did a lot of public service ads urging men to get tested for prostate cancer, noting that the PSA test had saved his life. More recently, he has been promoting Viagra.

What the Dole ads didn’t tell you, and most urologists won’t tell you, about prostate cancer screening is that there is a huge controversy over whether it actually saves lives at all. But even if we disregard the part of the evidence that says it doesn’t, the most optimistic version of the facts is that for every man whose life gets saved by PSA testing, there are 30-45 others who get treated for a prostate cancer that never would have killed them anyhow. And on top of that, most of those 30-45 others would never have even had a single symptom from that cancer during their lifetime. Now, what did the PSA test do for those 30-45 other men? It subjected them to radiation therapy or hormonal therapy (read chemical castration) or both. Of them, some fraction, variously 5-20% depending on which studies you like best, are left permanently impotent or incontinent as a result.

So Bob Dole may be a very satisfied customer, but maybe if his doctor had been more cautious, Dole wouldn’t need Viagra today.

Don’t misunderstand: some reasonable people may choose to take a 5-20% risk of incontinence or impotence for a 1 in 30 to 50 chance of avoiding a prostate cancer death. I’m not saying that choice should be legislated away on the existing evidence. But, frankly, the best place I know of where you can get a reasonable, clearly written, fair and unbiased presentation of the real risks and benefits of PSA screening, and almost every other clinical preventive service, is from a government agency: the US Preventive Services Task Force. (www.ahrq.gov)

Look, most of my research involves comparing the effectiveness and costs of different treatments. I do it for a living and I have honed my skills at it for decades and have access to the best information resources for doing it. Yet when I have to do it to advise family members, or even make the occasional health decision for myself, I find that if it isn’t an area where I already have expertise, the process is onerous and excessively time consuming. It would be a huge relief to have a panel of dispassionate, disinterested experts do that work for me and make it readily available in an easy-to-digest form. And I don’t know if the government is capable of forming dispassionate disinterested expert panels any more, but I know for sure that private industry will never do it.

It’s not necessary for a patient to see a physician for much preventive care. It can be provided by nurse practioners. For example, my local clinic-in-a- drugstore(part of a national chain) will do a basic physical exam for $99.00… that’s checking blood pressure, listening to your heart, lungs, reviewing meds, immunizations etc. Many insurance plans cover the services of these clinics.

So maybe we don’t need as many primary care docs as is thought.

StatsGuy, I agree with nearly everything you say here (and elsewhere, for that matter.)

But, really, “Comparing the efficacy of treatments and drugs with statistically robust samples of hundreds of thousands of patients. Measuring whether costly new procedures yield better outcomes. ”

You of all people should know how fraught with problems it is to compare efficacy or effectiveness of treatments from observational studies! Yes, these databases will be useful in many ways, and they will perhaps shed some light, indirectly, on comparative effectiveness–but their role in that will be, at best, ancillary.

And as for “commissions should be primarily staffed by doctors (with minimal conflicts of interest) that balance across regions, private practice, hospital staff, etc. “, why should we allow any conflicts of interest at all in this critical role?

Just to give some idea of how bad it actually is currently:

Recently I helped our local county set up a children’s mental health system that accessed Medicaid funds for private non-profit providers. Each state is different, but here in California the rate which providers are paid (by the minute) for services is decided BY THE PROVIDERS (who also until 3 years ago decided which potential clients were eligible for which services). It’s called “cost-based rate determination”. The provider simply provides whatever services, and at the end of the year they take all their costs and divide them by the number of service minutes to get a rate. It’s that simple!! Not surprisingly, there is great variance among rates for the same services from different providers. Also not surprisingly, it seems to cost $4-$5 per minute to provide even the most elementary services. Since staff can be hired to provide those services at $0.35 per minute, its UNBELIEVABLY PROFITABLE for the agency within which the service is performed (of course, it’s not officially profit, but like in for-profit health care and insurance most of the loot goes for gigantic salaries and huge expansion undertakings). I was proud to help kids get services but ashamed at how much the taxpayer was getting ripped off (Medicaid has no deductibles or co-payments, by the way, and is an entitlement that CANNOT BE RATIONED to those eligible). We lost control of health care costs at the precise moment, decades ago, when we decided that everyone must get all possible health care whenever someone decides they need it, and the more high-tech and costly it was, the better. This disaster is only speeded up by all the politicians in both parties declaiming that they are the ones who must understand how to protect the health care consumer’s absolute right to unlimited care at any cost.

I’m not sure you are drawing the correct conclusions. The problem seems to be that the provider determines the rate, not that the consumer is consuming too many services.

Are you saying that physicians can’t collect data for controlled studies?

Unless there is a profit cap of some sort.

I support single payer, but looking at alternatives I think that a hard % of premium cap on profits might reverse the incentive for the “insurance” companies more coverage for the money and use the market to the user’s advantage.

This would do nothing to address overall cost, however.

No, that’s not what I’m saying. With some training, most physicians can do that and can be recruited to gather data for clinical trials. Much cancer treatment research, for example, is done that way. (There’s a few who are incorrigible about taking shortcuts that degrade the data quality–but not enough to really matter). But data for controlled studies isn’t what’s going to be in the clinical electronic databases. It’s going to be routine medical data collect in haphazard, unstructured ways. There will be problems with missing data, misclassified data, all sorts of stuff. And of course, the comparison between people getting different treatments will not, in the clinical setting, be randomized, so inferences about comparative effectiveness will be murky at best.

Where I think the wide use of electronic medical records will prove really helpful is in providing early warnings of drug safety problems. Consider the Vioxx debacle. Vioxx was in widespread use by the time its association with increased risk of heart attacks was noticed. If we had universal, or near universal use of electronic medical records that interfaced well and if the FDA or researchers had access to that information (with suitable privacy safeguards enforced), we could have seen that coming much earlier. Now, again, due to lack of randomization and other problems with the quality of data you wouldn’t be able to immediately call Vioxx a problem–but with that alert in hand you could then quickly launch a better quality study and get your answer sooner than we did in the current situation. My best guess is that a few hundred lives could have been saved in this particular case.

I don’t want to overstate my differences with StatsGuy’s post. I agree with most of what he wrote there and I think he’s one of the smartest people who comments here regularly. And, frankly, if the same statement had come from James or Simon or another guest, I probably wouldn’t have bothered to remark on it. But StatsGuy really understands research issues, so I was truly shocked to see him make a claim that seems so blatantly misguided, and I couldn’t resist the impulse to comment on it.

Thanks for the lengthy reply. I am interested in what it would take for this data to be usable to you, so that’s why I am asking. If you have any more thoughts on this, I’d appreciate it greatly.

When I took my first course in health services research many years back, the lesson on day 1 was this.

Three desirable attributes of a health care system:

A. Unlimited access for all.

B. Unconstrained decision making for all patients and providers.

C. Stable, sustainable costs.

Pick ANY TWO, but you can’t have all three.

It’s not rocket science, but it seems we have spent the last 30-40 years trying to deny this simple basic law of economics.

When we started Medicare and Medicaid back in the 60’s it was a totally different zeitgeist from now. America was rich beyond imagination, and we believed that we could do anything we set our minds to. The only thing that stood between us and utopia was lack of political will. So nobody really cared about sacrificing C, and certainly organized medicine would have torpedoed the legislation if it didn’t provide for B. (They tried to anyway, but failed.) And A (at least for the elderly and poor–back then most of the rest of us could still afford reasonable health care) was the whole point.

Fast forward 40 years and, well, you know…

CBS from the West —

Thank you for the informed reply. You may well have changed my mind, or at least started me down that path.

Although I do remain skeptical of our government’s ability to “get it right”, or even to “get it less wrong”. But I admit I could be wrong about that, too.

Why would you say that Medicare is subsidized by private insurance, simply because private insurance reimburses at a higher rate? Couldn’t you as easily say that doctors fleece private insurance (which then turns around and returns the favor to its customers)?

Saying there is cross-subsidization implies that if there were no private insurance, Medicare rates would have to rise or doctors would exit the industry. But there’s no evidence of this; to the contrary, there are large and successful medical practices that derive the bulk of their revenue from Medicare.

One of the AMA’s many successful rhetorical devices has been anchoring the American public on the idea that they are underpaid by Medicare, as opposed to overpaid elsewhere.

I do not want to abuse a privilege to press my personal opinions in comments, and I believe you raise valid points. We do have some data on this issue, however. Much of it was gathered in different years, but it is worth reviewing…

http://www.nationmaster.com/graph/hea_phy_per_1000_peo-physicians-per-1-000-people

The data suggests that the US has a comparable number of physicians per capita as does the UK, Canada, or Australia. Less than France/Germany. The major differences, one must guess, are in how they are used (primary vs. specialty, treatment vs. research).

However, the trend line supports your argument more clearly… UK and Australia (not sure about Canada) have been increasing physicians per capita in the last decade, while the per capita number of physicians has been steady in the US (with, instead, a focus on increasing nurse practitioners and various substitutes).

One would anticipate some rise in consumption as the population ages (unless technology or business practices enable great efficiency), so the fact that total physician headcount per capita is flat (or possibly even slightly declining due to a retiring cohort in recent years) could be a serious issue that I did not address in the post above. Particularly in the last 5-8 years. I think the other issues mentioned in the post, however, do not lost any importance.

Thanks for the comment, I should clarify –

There are differences in types of statistical testing that are conducted in medicine. Prospective vs. retrospective, for instance. I am not suggesting that a database can replace clinical trials, or double blind testing. But it is a valuable data mining tool for isolating possible linkages (you cite Vioxx, but how many people suffered extensive bleeding from long term use of other more unregulated NSAIDS like ibuprophen before we even bothered to look?). Such a database also offers us the ability to gather data on new procedures (different surgical techniques) that is suggestive of trends. And, with proper modeling, to offer more conclusive findings for comparative treatments in some cases (this appears to be the controversial part).

One of the things that such a database would give us, for example, is a control group of… pretty much everyone. We have a better chance at identifying low-incidence side effects for drugs in long term usage (often, clinical trials end after a short period). As an example of the potential value of a national database, I would reference the Framingham Heart Study. Imagine something like that data (in many ways less complete, but in some ways broader/more inclusive) on a scale that was vastly larger.

I think you are primarily taking issue with the notion that we could make conclusive judgements on the comparative effectiveness of two drugs (or therapies) only using retrospective observational studies. Problems are significant – we can hope to control for variables (if we have measured them) but we still have problems like self-selection (perhaps a new therapy is being tried more often by people who are harder to treat?). I acknowledge the challenges, but I think in some cases, with proper modeling (controls, instrumental variables, case matching), we could gather compelling evidence.

Consider – if we merely conducted analysis at the hospital or physician level (rather than the patient level) using approximately matched pairs, and looked at outcomes vs. treatment tendencies (as we know, some doctors or hospitals use preferred treatments simply because they are available or were historically used, rather than because of a difference in patient profiles)- we might hope to isolate some (approximately true) measures of causation.

At least, that would be my hope.

Statsguy, I can’t imagine how with all possible data from all patients, new types of ways of removing bias couldn’t be devised. Can you speak to that?

To put it another way, how could it be that randomized carefully controlled double-blinded studies on specific hypotheses over long time-frames always trump the sum total of all accumulated data and experience. And, I’m not looking for a statistical justification–I’m talking about what makes for good medicine.

The thing about retrospective observation based studies is that you can almost always argue about something. So a lot comes down to determining which assumptions are plausible, and that comes down to judgement. But we do have better tools for managing things like missing data, missing variables, and multi-causation than we had 20 years ago.

Also, clinical trials can have their own problems. Among other things, the cost of such trials causes some companies to conduct them elsewhere (India). That means a different population, with different dietary habits, different levels of chronic disease, and different genetic traits. Plus you have enrollment and fallout.

But at least the process is somewhat standardized. Retrospective statistical analysis is almost an art form by comparison. But, I think, still quite valuable, and in some cases fairly conclusive. CBS is probably right that I oversimplified, though.

Yakkis, I’m a bit puzzled by your saying in reply to me that single payer would save lives, as if you were contradicting me when in fact that was my point, not to mention PNHP’s for a couple of decades. As you said, let us be clear: H.R. 676 IS the single-payer bill. H.R. 3200 in its present form is candy for “health” and insurance companies, whose stocks went up after it made it through committee.

I didn’t mean to sound like I was contradicting you!

I mean to say to you: “go guys(and gals), go!”

There are bottlenecks at educations of higher learning for nursing and other skilled care. Many people are turned away from getting degrees that would make excellent caregiver or caretakers. See Urban Institute report here: http://www.jonascenter.org/

And so we do! So far, I believe, the practice of biting off opponents’ fingers has not spread beyond California, and I hope it will not–unkind, and I doubt its political efficacy. There is more value in asking your representative to support the Weiner amendment, which would substitute the text of H.R. 676 for Division A of H.R. 3200, effectively turning it into a single payer bill.

Thanks for all your thoughtful comments on this topic!

“I think you are primarily taking issue with the notion that we could make conclusive judgements on the comparative effectiveness of two drugs (or therapies) only using retrospective observational studies.”

Yes, that is exactly what I was taking issue with. Thank you for your post. And I agree entirely with what you have said in this reply.

Employer Tax Deduction for Employee Health Insurance Must End

There is one issue in this health care debate that has gotten almost no press. When the issue of the HIGH COST of health insurance and the high cost of health care and drugs are discussed there is never any mention of the employer tax deduction for employee health insurance. My understanding of the effects of this tax deduction is that this is the primary cause of the high cost of insurance and care. The fundamental reason is that the individual citizen (i.e. the employee) is separated from his health care dollars. Each employee is not allowed to “vote” with his dollars for the most cost-effective health insurance, and indirectly health care, that meets his/her needs. Because of this there is no market place for health insurance. Instead the health insurance companies have complete control of the health insurance market through employer paid health insurance, which is subsidized by taxpayers through this tax deduction. Health insurance companies, and American Big Business in general, do not want an active, critical, citizen/employee-based, market place. When someone else (i.e. taxpayers) is paying part of the bill there is no reason for the purchaser (i.e. the employer) to strike the very best bargain.

Without this tax deduction there would be no reason for employers to provide health insurance. Without this tax deduction we would have a true health insurance market place at the citizen level. As long as this tax deduction is in place there will be no significant improvement in the cost of insurance and care. I do wonder why economists do not focus on this tax deduction in their many analyses of the economics and cost of health care. My speculation is that conservative economists don’t mention it because they believe eliminating this tax deduction would be bad for health insurance companies, and American Big Business in general, while liberal or progressive economists don’t mention it because they believe that eliminating this tax deduction would work against the individual employee/citizen because they believe the employer would not increase wages by their current cost of health insurance. So what I suggest we have here is a case of a very unhealthy co-dependency on a tax deduction that has driven health insurance and care costs to their highest possible levels. A co-dependency not unlike a drug-centered co-dependency. And of course there is the co-dependency between members of Congress and the health insurance industry.

I’m well aware this is not a trivial issue. The employer tax deduction for employee health insurance is the single largest tax deduction, significantly larger than the tax deduction for home mortgages. A solution would be for Congress to eliminate this tax deduction by reducing the deduction by an equal amount over five years. This would allow employers, health insurance companies, and employees/citizens to develop a new cost-benefit equilibrium over the next five years. Of course members of Congress currently receive considerable sums from the health insurance industry. Eliminating this tax deduction would serve to reduce those campaign contributions and lobbying efforts considerably since the health insurance industry would no longer have to “protect’ this tax deduction. In summary, we currently have high cost health insurance and care and drugs because Congress has given away, and continues to give away, tax-payer dollars via a tax deduction. This would constitute REAL CHANGE in our political and corporate cultures.

I am in support of a single-payer non-profit health insurance company. If that is not politically possible, then I am in support of a public non-profit health insurance company to compete with for-profit health insurance companies. Under NO circumstances should there be a law REQUIRING every citizen to purchase health insurance, which I think would be UNCONSTITUTIONAL.

Oh yes, healthcare rationing is just so wonderful. Here is a heartwarming article from the Daily Telegraph about how many patients misdiagnosed in the absolutely fabulous British healthcare system as dying are left uncared for:

“In a letter to The Daily Telegraph, a group of experts who care for the terminally ill claim that some patients are being wrongly judged as close to death.

Under NHS guidance introduced across England to help doctors and medical staff deal with dying patients, they can then have fluid and drugs withdrawn and many are put on continuous sedation until they pass away.

Related Articles

Dying patients

Number of NHS patients given wrong medicine doubles

Third of patients ‘being treated by nurses’

1 in 10 NHS jobs need to be cut

Are we killing our elderly?

What is the Liverpool Care Pathway?

But this approach can also mask the signs that their condition is improving, the experts warn.

As a result the scheme is causing a “national crisis” in patient care, the letter states. It has been signed palliative care experts including Professor Peter Millard, Emeritus Professor of Geriatrics, University of London, Dr Peter Hargreaves, a consultant in Palliative Medicine at St Luke’s cancer centre in Guildford, and four others.

“Forecasting death is an inexact science,”they say. Patients are being diagnosed as being close to death “without regard to the fact that the diagnosis could be wrong.

“As a result a national wave of discontent is building up, as family and friends witness the denial of fluids and food to patients.”

The warning comes just a week after a report by the Patients Association estimated that up to one million patients had received poor or cruel care on the NHS.

The scheme, called the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP), was designed to reduce patient suffering in their final hours.

Developed by Marie Curie, the cancer charity, in a Liverpool hospice it was initially developed for cancer patients but now includes other life threatening conditions.

It was recommended as a model by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (Nice), the Government’s health scrutiny body, in 2004.

It has been gradually adopted nationwide and more than 300 hospitals, 130 hospices and 560 care homes in England currently use the system.

Under the guidelines the decision to diagnose that a patient is close to death is made by the entire medical team treating them, including a senior doctor.

They look for signs that a patient is approaching their final hours, which can include if patients have lost consciousness or whether they are having difficulty swallowing medication.

However, doctors warn that these signs can point to other medical problems.

Patients can become semi-conscious and confused as a side effect of pain-killing drugs such as morphine if they are also dehydrated, for instance.

When a decision has been made to place a patient on the pathway doctors are then recommended to consider removing medication or invasive procedures, such as intravenous drips, which are no longer of benefit.

If a patient is judged to still be able to eat or drink food and water will still be offered to them, as this is considered nursing care rather than medical intervention.

Dr Hargreaves said that this depended, however, on constant assessment of a patient’s condition.

He added that some patients were being “wrongly” put on the pathway, which created a “self-fulfilling prophecy” that they would die.

He said: “I have been practising palliative medicine for more than 20 years and I am getting more concerned about this “death pathway” that is coming in.

“It is supposed to let people die with dignity but it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Patients who are allowed to become dehydrated and then become confused can be wrongly put on this pathway.”

He added: “What they are trying to do is stop people being overtreated as they are dying.

“It is a very laudable idea. But the concern is that it is tick box medicine that stops people thinking.”

He said that he had personally taken patients off the pathway who went on to live for “significant” amounts of time and warned that many doctors were not checking the progress of patients enough to notice improvement in their condition.

Prof Millard said that it was “worrying” that patients were being “terminally” sedated, using syringe drivers, which continually empty their contents into a patient over the course of 24 hours.

In 2007-08 16.5 per cent of deaths in Britain came about after continuous deep sedation, according to researchers at the Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, twice as many as in Belgium and the Netherlands.

“If they are sedated it is much harder to see that a patient is getting better,” Prof Millard said.

Katherine Murphy, director of the Patients Association, said: “Even the tiniest things that happen towards the end of a patient’s life can have a huge and lasting affect on patients and their families feelings about their care.”

I believe you have violated copyright law quoting such a large passage.

Perhaps though the Daily Telegraph will forgive you since they are a conservative paper.

In large populations, for each plan offered on a national exchange, a “community” rate for the consumer can be risk-adjusted at the insurer level for the population that insurer attracts. Those risk adjusters only work well when applied over a population of many thousands. That is one of the crucial reasons for a national exchange with at least 20 million total lives spread across a number of private plans and, hopefully, a public option as well.

And, if we add a discumbobulator pump here, and a layer of bureaucracy there, and an independent board over there, and incent like this, and manage like that, tweak here, a little bailing wire there, some duct tape over here, and apply the confusion backwards principle…..

Sorry James, I agree with 93.7% of what you say, but not this time.

Private Heath Insurance has failed. Private hospitals have failed. the AMA that creates scarcity by keeping the number of medical schools very low, and the graduation standards high, has failed-the US has some of the lowest MD levels per capita in the industrialized world. The US single handedly subsidizing the worldwide profits of the Pharma companies, and not negotiating prices has failed.The whole system has failed. It doesn’t work. 60% of all personal bankruptcies can be tied directly to healthcare expenses-the vast majority of these folks are insured.

The United States is the ONLY industrialized, or even “civilized” country that does not have a single payer system that covers everyone. Why does the US continue to engage in yoga-esque gyrations and other un-natural acts in a continuing insane attempt to try to make a horribly inefficient, expensive, and terrible system, that doesn’t even provide quality care, work?

Translated, why are we so fixated on making sure Big Pharma, Big Health Insurance, Big AMA, and the Big Hospital and Health Care industrial complex stays profitable? They all have failed. Miserably. Costs have exploded. Care is not better, and maybe in all probability, worse. They all had their chance. They all have proven unworthy of leading the way forward.

The smartest thing to do is accept this, and move on. Single payer. Does the US really think that it knows something the rest of the industrialized world doesn’t? France’s system is half as expensive as the US’s, and provides the #1 ranked healthcare in the world. Denmark. The Netherlands. Britain. Canada. Australia. Panama. All single payer. All much less expensive than the US system.

I know a fair bit about this topic as my wife is Canadian, and my kids are duel citizens. And, I roomed with a Dutch resident when I lived in Holland. Having used the Dutch, Canadian, and Panamanian healthcare system personally, I’d take any of these any day over the US system.

“The question is not whether we will have rationing – the question is how to structure a system of rationing that accomplishes our goals.”

This sort of presumes we have some collective goals — “our” goals. I agree with some of your goals, but not with others.

One of my goals is to keep my money and spend it on the health care I choose. Right or wrong, the resources belong to me, and I should not be forced to buy an insurance policy that does not fit MY goals. The statist solution will limit my access to holistic care, which is what I prefer. I think people should be free to spend their own money on ineffective care or effective care, or care that makes them happy, but is ineffective. I do not believe that two parties should get together and decide how to spend a third party’s money.

To the statist, this is incomprehensible. I don’t even know why I bother to bring it up. It appears that most have swallowed the collectivist, statist argument, and anyone raising a finger in protest will have it bitten off.

This is all based on the notion that “health care is a right.” I agree, it is a right. Like free speech. Does that mean the government is obliged to give everyone a megaphone and a printing press?

So asks the voice in the wilderness.

eric “One of my goals is to keep my money and spend it on the health care”

Well good for you… and I am sure that among Madoff’s clients there were many that shared the same goal.

Me? My goal is always to be healthy and not have to spend one dime on my health but, since my goal is sort of ambitious just in case I spend some money on health insurance. In doing so I am perfectly aware that I run a counterparty risk since, the day I might need my insurance company to step up to the plate, it might not be there, having lost it all pursuing some super-safe AAA investments. If that would happen, let us hope it does not, I would have to use whatever resources of my own I have available or rely on the government.

Should we all carry a tattoo that puts us all in two camps, those who do not mind some government help in health issues and are willing to spend some taxes on it, and those who truly want to fight out come rain come shine? I say it because I have often seen how many of the “I do it on my own” machos are the first furious about the State not being there when needed.

I do not believe that two parties should get together and decide how to spend a third party’s money.

Maybe you’d like to live in a country without taxes? Without government?

I say it because I have often seen how many of the “I do it on my own” machos are the first furious about the State not being there when needed.

I have no problem with letting these guys have a separate system just for them. In practice this is exactly what happens; they go on “medical tourism” whenever they need non-immediate health care.

If our friend Eric wants to shoot himself with a gun as a pain or cancer remedy, I certainly wouldn’t try to stop him. Just don’t make me pay for the cleanup or burial costs!

What I mean to say is that suicide remains a popular “alternative remedy” for people with severe chronic pain and cancer, but it’s not one that the government will ever pay for.

Eric, a step in the direction you are suggesting would be to eliminate the employer tax deduction for employee health insurance. It is my belief that this the primary reason health insurance and health care are so expensive. The individual employee/citizen has been separated from his health care dollars. Once the tax deduction is eliminated there will be a true market place for health insurance and health care. As it is now employers and health insurance companies control the market, which is what all big business wants. Big business abhors a true free market place, they want control. Of course it will not be easy eliminating this tax deduction. It is the single largest tax deduction; larger than home mortgage interest deduction. Write your members of Congress and Obama. Tell them to eliminate the employer tax deduction for employee health insurance.

Here are some problems with your thesis that have to be addressed:

1) In a free market economy, it is impossible to use centralized control of pricing in one sector (health care) as a means of cutting costs. The British model uses this strategy and it results in triaging the elderly to the mortuary. Literally, people are chronically sedated until they die. The cancer survival rate in Britain is dismal because the system refuses to use the most advanced (expensive but effective) treatments. As it is, applications to medical school are down across the board, and have been for years. Not many want to be a physician in a single payer system, or something akin to that. It costs ten years of lost income to become a physician, plus med school loans of over $100K. What you propose would make it impossible for a physician to recover the cost of their “investment” for many more years. In contrast, an attorney has to invest only seven years and his/her fees are not constrained by a government bureaucracy. Likewise for most professionals. Do you really want to be in the business of deciding what is a “fair” reimbursement for a physician? Basic economics dictates that even an occasionally irrational marketplace is a better master than an “all knowing” government. Introducing honest to goodness price competition into the system, at least for some of the more expensive things, would be more effective.

2) True, our current system is inefficient and can reward physicians who order unnecessary tests and procedures. And, the use of the ER for care of the uninsured is nuts. However, trying to force “best practices” as dictated by some kind of omnibus review board is a pipe dream. There is an onslaught of “outcomes” type studies covering everything from influenza to hypertension and they often provide conflicting and contradictory results. What one study indicates as an effective treatment can be overturned by a different study that comes out even months or a few years later. No gaggle of bureaucrats has even a hint of a chance at dealing with this properly. The process will be controlled by politics, as the disease “du joir” gains favor at the expense of some other afflictions. Example: breast cancer and HIV are the politically correct places to seek research funds. You propose to fix the structural inefficiencies of our health care with something that looks fine on paper but is itself also messy and open to political and bureaucratic foibles. Medicare has minimal restrictions on conditions covered and that is why it is expensive, but it would ignite a rebellion amongst the elderly if coverage became “basic”.

3) Your proposal to provide basic coverage to everyone and allow those who can afford it to purchase supplemental insurance is intellectually honest, but it isn’t even the way Medicare works. What do you mean by “basic”? A chest xray if you have a bad cold is covered, but if you have cancer you can only get the least expensive chemo? You see, getting into the dirty details always leads to the same conundrums that afflict socialist systems. If it was possible to clearly define what’s covered and what’s not in a “basic” plan and then effectively deal with all the civil rights and other lobbyists who would be raising hell over things not covered, that proposal could work. Good luck with that.

Your arguments have been discussed before. Please scroll up.